Ask for Evidence infographic

If you’re not sure about something you’ve read or seen, follow these simple steps to #AskforEvidence? [...]

No matter what the scientific study, at some point scientists have to use statistics to interpret their results, and form their conclusions.

Unfortunately, scientists can be as bad at statistics as the rest of us, and dodgy statistics can be used and abused (either by mistake or deliberately) to make studies look like they reached conclusions that they certainly did not.

This article doesn’t require you to know anything about statistics, but does outline some key concepts and questions that will help you judge whether a claim is statistically sound or not.

Significance

Statisticians check if results from a study are ‘statistically significant’, which is essentially a measure of how sure they are that the results aren’t simply down to chance.

Confusingly, the word ‘significant’ in the context of statistics means something quite different to how we’d normally understand it. If a result is ‘statistically significant’, this doesn’t mean it is practically significant or of any importance to society. It just means that, mathematically, the result is not likely to be pure chance. The result might, in real terms, still be absolutely tiny and of no particular importance.

So, don’t be fooled if you see the words ‘statistically significant’. Still ask: is it significant in the real world?

Regression to the mean

A footballer scoring hat-tricks in a couple of matches is likely to return to scoring his usual number of goals over time.

In the same way, when a scientific study gets a large or dramatic result that is way off the average, ‘regression to the mean’ is the tendency following an extreme measurement for further measurements to be closer to the average.

So just because one study has found a strong effect it doesn’t mean studies will always find a strong effect. In fact, it is unlikely.

Outliers

An outlier is an extreme number from a range of possible values.

If someone was advertising a competition with a range of prizes, for example, they might say something like ‘you could win up to £2,000’. That’s going to be the biggest prize – all the other prizes are likely to be much smaller.

In a similar way, to make a science story more dramatic, people regularly use the most extreme number from a range of values in studies. That is, an outlier – a possible but not very likely value. So watch out for phrases like ‘as much as’ or ‘up to’.

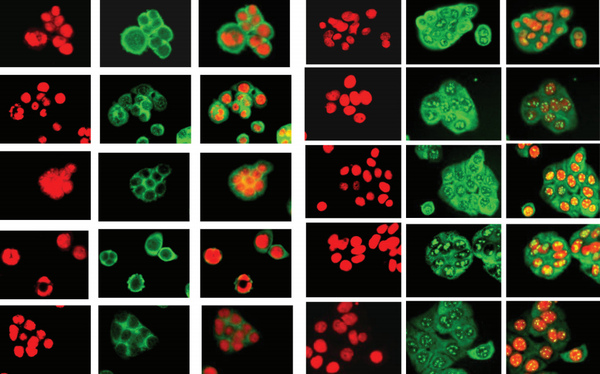

Relative and absolute risk

Reporting a percentage increase in risk without including the actual (absolute) risk can make a result sound far bigger or more alarming than it really is. To understand whether a change in risk matters, you need to know how big the risk was to begin with. If a risk was small to begin with, a big percentage increase isn’t necessarily dramatic or alarming.

Share this graphic explaining the difference between relative and absolute risk:

If you’re not sure about something you’ve read or seen, follow these simple steps to #AskforEvidence? [...]

I’ve been Asking for Evidence for a couple of months now and it’s interesting how organisations respond to it. I’ve had an array of responses: Polite but dismissive….. First up [...]

Every month there are dozens of news reports about medical breakthroughs and wonder drugs. The internet is cluttered with adverts and chat-room conversations testifying to ‘amazing’ benefits. [...]

Politicians like to claim a lot of things, from how they’ve reduced unemployment to how they plan on investing in renewable energy, but how prepared are they to provide the [...]

There is a system used by scientists to decide which research results should be published in a scientific journal. This system, called peer review, subjects scientific research papers to independent [...]

If someone asks you something and you don’t know the answer, what do you do? You Google it. The internet is one the most powerful tools at our disposal, and [...]